Here are five revitalization myths that have plagued downtown Jacksonville and the surrounding urban core neighborhoods for the last 30 years.

1. Over-reliance on high-profile, “sexy” projects

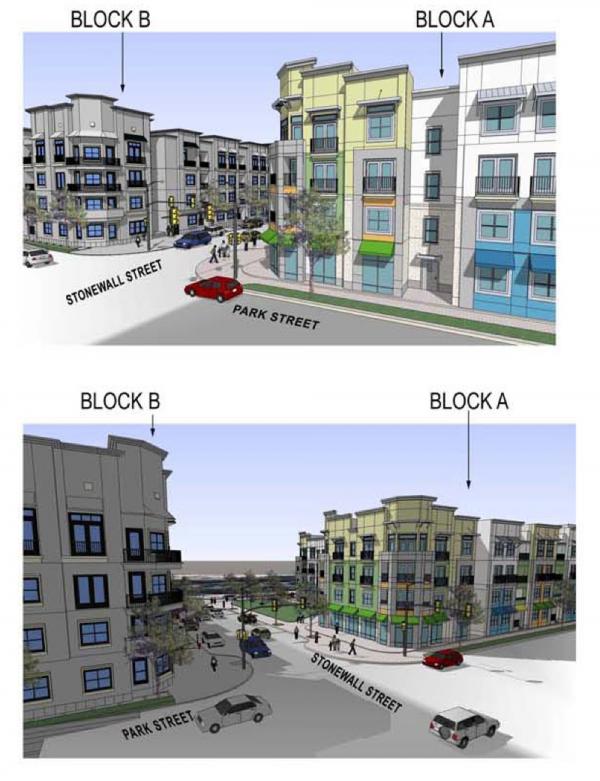

Instead of facilitating small-scale redevelopment concepts, higher focus has historically been given to large-scale projects like Brooklyn Park - as the keys to downtown vibrancy.

There is a commonly-held belief that cities can build megaprojects that will catapult their downtowns into the international spotlight, and trigger a wave of prosperity in their wake. In reality, even when such projects are independently successful, they're never the one-trick-pony that was originally imagined.

Jacksonville should know this better than ever. The conversion of Hemming Plaza, Skyway Express, Duval County Courthouse, LaVilla's redevelopment, Landmar's Shipyards, Mile Development's Brooklyn Park and the Prime Osborn are all examples of major "one-trick-ponies" that would instantly breathe live into a morbid downtown. Despite hundreds of millions invested, Jacksonville's downtown core has continued to decline. With this in mind, we should proceed cautiously with the idea that a new Northbank convention center alone is the key to downtown's revitalization. While a well-designed, mixed-use center that's seamlessly integrated with its surroundings can be a positive impact, in reality, it's an expensive solution to one of several ailments that currently afflict our downtown.

Five years after the demolition of several historically significant structures to make way for Brooklyn Park, this area of the urban core is worse off, as the Brooklyn Park project never made it off the ground.

2. Unhealthy fascination with unique, charismatic civic leaders

LaVilla was the first urban African-American city in the state, the site of the first recorded blues song, and eventually became known as the 'Harlem of the South'. Somewhere along the line, Jacksonville's citizens were convinced ripping this neighborhood to shreads was the most successful way of restoring it.

Everyone loves a superstar, charismatic, influential civic leader. However, despite success in their personal and professional lives, it's important to realize that they are human like the rest of us and may not actually have all the right answers when it comes to understanding urban neighborhood history, and social, economic and development patterns. Ignoring this critical fact can lead to disastrous results, such as the complete destruction of LaVilla, Sugar Hill, Brooklyn and the separation of Springfield from downtown.

Nearly 20 years later, this once proud community seems like a perfect set for "I Am Legend 2", instead of the promised, culturally rich district where people would like to live, work and play.

3. Misapplication of other cities’ approaches

The Jacksonville Landing was supposed to return downtown Jacksonville to economic stability after the success of a similar festival marketplace in Baltimore.

It is often assumed that because Idea X worked in City Y, it will be equally successful in City Z. This isn't always the case. For example, the Jacksonville Landing was developed as a downtown revitalization project based on the success of a similar center in Baltimore's Inner Harbor. However, the surrounding context of complementing uses had more to do with the success of Baltimore's Harborplace than the concept of placing a shopping center on a downtown waterfront did. Twenty-four years later, while Baltimore has continued to cluster their Inner Harbour with a dense connection of complementing uses, the Jacksonville Landing still struggles, partially because of a layout that doesn't fit well with the surrounding environment and the lack of a city plan to continue clustering the immediate area with complementing uses. The lesson to be learned here is that whatever we observe and decide to implement from other cities must be applied in a manner that fits with the needs and layout of our local setting.

By not realizing the importance of pedestrian-scale urban design with the surrounding context, Jacksonville overlooked the fact that Harborplace's (Baltimore) courtyard visually opens up directly to the surrounding urban environment.

4. Descent into a cycle of self-recrimination

Older urban core industrial areas are ideal for market-rate, small-scale, innovative, adaptive reuse projects due to the availability of large spaces at an affordable cost.

Jacksonville is the definition of a red-headed stepchild. Many innovative and creative ideas that can take the city to the next level are shot down quickly because of a dominant thought that things won't work in Jacksonville because it's different from everywhere else. In addition, many things never have the opportunity to take place because of over-regulation of city policies. In the meantime, communities with less desirable natural and logistical assets such as Charlotte, become economic powerhouses overnight because of a "can-do" attitude and a willingness to embrace change.

Unfortunately, many of urban Jacksonville's obsolete, historic, industrial areas remain abandoned, underutilized and stagnant, due to industrial-preservation-based city policies that are intended to keep the things that created Portland's Pearl District, Denver's SoHo, Tampa's Channel District and Atlanta's Castleberry Hill from never taking place around downtown and throughout the Northside.

5. Resignation to superficial changes

There is a local belief that spending millions to install brick pavers, expensive palm trees and replica historic lighting to urban core streets stimulate economic prosperity.

Cities have a long and storied history of believing in the power of cosmetic changes only to be let down by the results. Jacksonville is no exception. After spending millions on "town center" streetscape beautification projects over the last decade, the only commercial districts that can be considered a success are the ones that were already vibrant before streetscape money was used to enhance them. Those that struggled beforehand, still struggle today with the exception being that they now have unmaintained streetscapes to go along with their original revitalization challenges. Making streetscapes attractive has its merits, but we should not get tricked into thinking cosmetic changes have a direct correlation with economic prosperity.

Struggling neighborhoods like the Eastside (Philip Randolph Blvd. above) and Lackawanna illustrate that cosmetic changes, such as streetscapes, don't guarantee economic vitality.

Conclusion

By no means does this indicate that all is lost for the future of downtown Jacksonville and the surrounding communities. However, these examples do suggest that if we are serious about bringing our core back to life, it will require doing the exact opposite of what city and civic leaders have believed and promoted over the last few decades.

This article is a Jacksonville-specific variation of Brendan Crain's "Five Innovation Myths Applied To Urbanism."

http://www.urbanophile.com/2011/06/21/five-innovation-myths-applied-to-urbanism-by-brendan-crain/

Article by Ennis Davis.

41 Comments so far

Jump into the conversation